DHR History

Learn about some of the pivotal moments that have

defined our journey in protecting the rights of all New Yorkers.

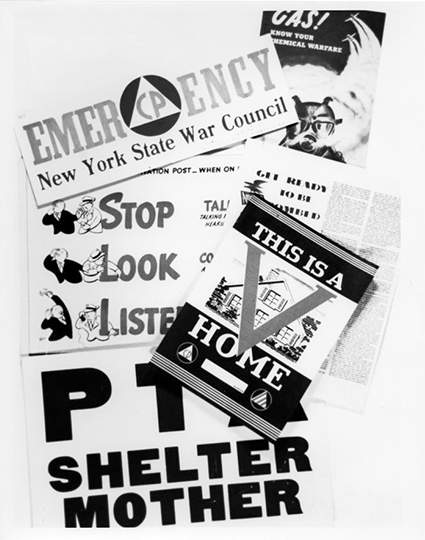

DHR’s roots go back to World War II when the State War Council formed the Temporary Committee on Discrimination in Employment. The Committee's work led to a groundbreaking achievement—the Ives-Quinn Anti-Discrimination Bill.

The Ives-Quinn Anti-Discrimination Bill was signed into law by Governor Thomas E. Dewey. This made New York the first state to pass legislation banning employment discrimination based on ethnicity, creed, skin color, or national origin. The state created the State Commission Against Discrimination (SCAD) to enforce this law, setting a national precedent.

Elmer A. Carter, appointed as Chair by W. Averell Harriman, played a crucial role in shaping the newly formed SCAD and developing the agency’s legal authority in civil rights enforcement. Under his leadership during the burgeoning civil rights movement, the agency expanded its fight against employment discrimination, solidifying New York’s role as a pioneer in addressing racial discrimination. Carter’s work laid the foundation for the expansion of the Human Rights Law in the 1950s to cover housing and places such as restaurants, hotels, hospitals, and other public places.

The Human Rights Law was expanded to include housing, broadening the scope of anti-discrimination protections in New York.

SCAD prevailed in Patricia Banks’ discrimination case against Capital Airlines. With the support of SCAD, Banks proved that the airline had discriminated against her based on her race, leading to an order that she be offered a job. Her victory followed a similar case brought by Ruth Carol Taylor in 1958, who became the nation’s first black flight attendant after challenging TWA’s discriminatory hiring practices. Both women’s fights for equality are recognized in the National Museum of African American History.

The State Commission Against Discrimination (SCAD) was renamed the New York State Commission for Human Rights.

In 1968, under the leadership of Commissioner Robert Mangum, the agency was reorganized and renamed the New York State Division of Human Rights, and the law was renamed the New York State Human Rights Law. As commissioner, Robert Mangum took decisive action to eliminate racial imbalances in housing and employment, and DHR:

Secured commitments from real estate firms to end discriminatory practices

Persuaded one of the world’s largest energy companies, Consolidated Edison, to stop gender-based pension discrimination

Ordered a minor-league baseball league to hire the first female umpire in the United States.

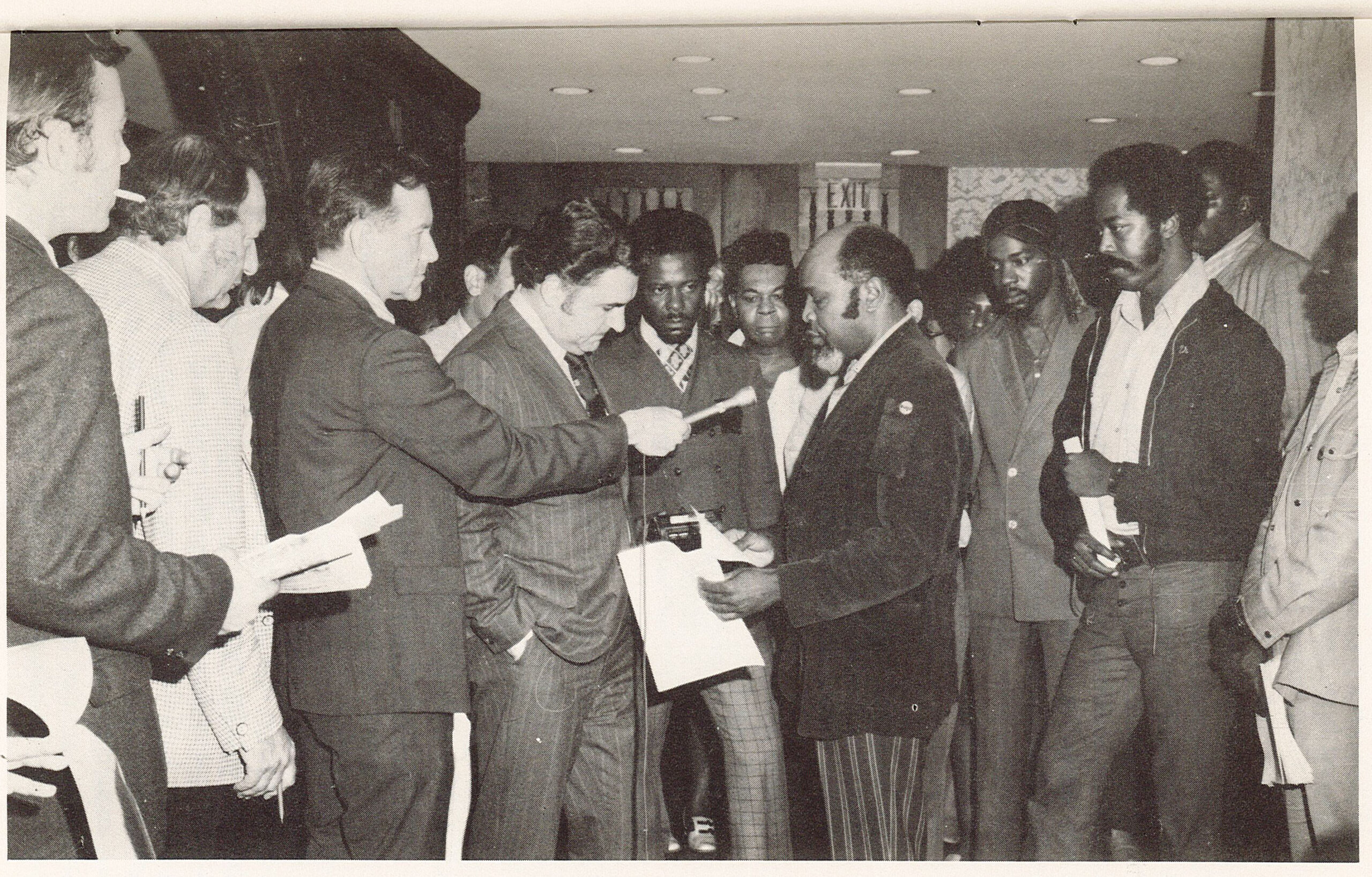

Commissioner Jack Sable met with community organizations as part of the state’s response to the Attica Prison riots. His outreach demonstrated the Commission’s commitment to address civil rights concerns and improve conditions for incarcerated individuals.

The Human Rights Law expanded to prohibit discrimination against individuals with disabilities, marking a major step toward inclusivity in employment, housing, and public accommodations.

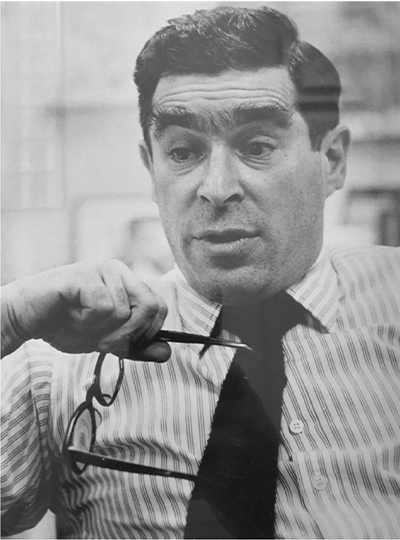

Commissioner Werner Kramarsky championed rulings that advanced fairness and accessibility in the workplace and beyond:

Banned height requirements for corrections officers

Ensured wheelchair users could compete in the New York City Marathon

Mandated that job applicants could not be denied employment for based on a weight-related medical condition or in drug treatment programs

Under Commissioner Margarita Rosa, DHR processed the first full administrative hearing in the US for HIV-related discrimination. This set the national precedent for protecting individuals with HIV/AIDS from workplace and housing discrimination.

DHR fought for 44 women at Macmillan Publishing, challenging unfair pay, titles, hiring, and promotion practices that disadvantaged women and minorities. Macmillan agreed to a consent decree with the EEOC, leading to meaningful change. The outcome included career counseling and development programs, tuition assistance, seminars, and financial relief—creating a fairer workplace for women and other targeted groups at Macmillan.

DHR celebrates 40 years of advancing human rights and fighting discrimination. Pictured in the back row are former commissioners who helped shape the agency’s legacy of advocacy and justice: Robert R. Shaw, Robert J. Mangum, George H. Fowler, and H. Carl McCall.

Geoffrey Bowers, a gay New York attorney, made history when he stood against injustice by filing one of the first AIDS discrimination cases. He alleged that he was fired from his job at Baker & McKenzie because he had been diagnosed with Kaposi’s sarcoma and AIDS. After filing a complaint with DHR, the court ruled in his favor, shining a light on AIDS discrimination and setting a legal precedent. This landmark trial is widely believed to have inspired the 1993 film Philadelphia, starring Tom Hanks.

The Human Rights Law expanded to include protections against housing discrimination for families.

DHR changed the law to mandate that employers provide reasonable accommodations for workers with disabilities.

Protections for religious practices and observances were added under the Human Rights Law.

DHR added sexual orientation and military status as protected categories under the Human Rights Law.

The Human Rights Law was amended to protect domestic violence victims from workplace discrimination.

Sexual harassment against domestic workers based on gender, ethnicity, religion, or national origin was added as a protected category under the Human Rights Law.

DHR granted protection to unpaid interns from workplace harassment.

DHR expanded the Human Rights Law to include sexual harassment protections for small businesses with fewer than four employees. The law was also amended to prohibit employers, employment agencies, licensing agencies, and labor organizations from discriminating against workers based on familial status. This expansion of the law also included the requirement that pregnant employees must have reasonable workplace accommodations.

DHR adopted regulations to prohibit discrimination based on gender identity or transgender status.

Changes in the Human Rights Law included restoring DHR’s authority over public schools and making “lawful source of income” a protected category in housing. The Gender Expression and Discrimination Act (GENDA) affirmed gender identity and expression as protected categories. Additionally, prior arrest protections were extended to housing and volunteer positions, including traits like ethnic hair textures and hairstyles.

Upholding Human Rights Amid a Global Health Crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic had a tremendous impact on New Yorkers. Acts of bias and discrimination continued throughout the public health emergency, underscoring the importance of the Human Rights Law’s protections during this uncertain time. DHR adapted to changing circumstances during the pandemic and continued its work upholding the rights of all New Yorkers.

In response to the drastic uptick in discrimination and violence targeting Asian American and Pacific Islanders that occurred during the pandemic, DHR engaged in programming and events state-wide to address the effects of this bias. DHR also implemented an expedited process for investigating and resolving COVID-19-related discrimination complaints.

Governor Kathy Hochul signed legislation extending the statute of limitations for filing discrimination complaints with DHR. Effective February 15, 2024, individuals now have three years to file complaints, strengthening access to justice for all New Yorkers.

DHR continued to strengthen protections across the state. Governor Hochul directed DHR, in partnership with New York State Homes and Community Renewal (HCR), to launch a new unit focused on resolving Section 8 voucher discrimination complaints. This initiative aims to ensure that voucher holders can access housing without illegal barriers.

DHR also received over 7,000 discrimination complaints in the 2023 fiscal year. DHR introduced a pilot program focusing on early mediation to improve access to justice, helping resolve issues faster and at a lower cost through voluntary participation and trained mediators from Community Dispute Resolution Centers.

Recognizing that young people are often at the forefront of combating hate and bias, DHR’s Hate & Bias Prevention Unit launched an initiative to engage and empower youth. This program helps inspire the future generation of leaders dedicated to fighting discrimination and promoting inclusivity in communities.